An inside look at the VSE’s freshly launched policy paper ‘National Framework for Comprehensive Victim Support’

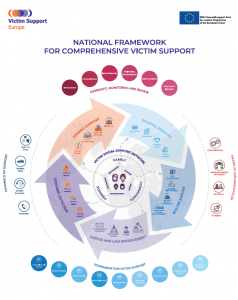

As people, and as a culture, Levent Altan, Executive Director of Victim Support Europe (VSE), says, we would be much healthier and happier if we reformed how we help victims of crime. VSE’s recent publication, the “National Framework for Comprehensive Victim Support”, offers up truths about the current state of victim support in the EU and asks the question “What defines excellence in victim support?”.

On 16 November, Victim Support Europe and Saskia Bricmont co-hosted an event on the “Vision for a revised Victims’ Rights Directive” to officially launch the new policy paper the “National Framework for Comprehensive Victim Support”; a testament to how practice- and evidence-based policymaking is driving improvements to the victim support system in Europe.

As the European Commission intends to publish an amended Victims’ Rights Directive in early 2023, now is the time to raise awareness of and talk about this topic. Ten years after the first Directive, a review is needed to strengthen existing victims’ rights, and to establish both clearer Member State obligations and new rights for victims. The paper offers reasons why the existing approach to victim support has to be revised and suggests a forward-looking model for victim support in the EU.

We sat down with the VSE’s Executive Director, Levent Altan, and Policy Officer, Léa Meindre-Chautrand, to get the inside scoop on this important milestone.

Yesterday, Victim Support Europe introduced the ‘National Framework for Comprehensive Victim Support’ paper to key EU stakeholders: Why do you think victim support requires a framework?

Levent Altan: In any democratic society, there is the danger that people think rights merely exist, with no effort required to keep them going. But democracy, fundamental rights and a victim-focused response to crime requires active citizenship and a concerted State effort. We all have to work, together, without interruption to achieve support for victims. The moment we stop working on it, stop improving it, it degrades or becomes redundant. Victim support is behind the times but is such an essential service that it has to be brought into the 21st century. Victim support is something we have to learn to ‘do’. It’s not just a right that’s written in law. It’s not just enthusiasm and skills offered by volunteers. Victim support requires tolerance, collaboration, and coordination, so the more strategic and united we can be, the better we can address the needs of all victims.

Support is an essential service, a bridge between health and justice. We, governmental and non-governmental agencies, must have a strategic long-term approach; an approach which is agreed, and funded, at the national level in coordination with multiple victim support actors. We can then identify the victims, we can help them access the services they need, we can raise their awareness of existing services, and we can all work together more coherently. These are the aims of the National Framework for Comprehensive Victim Support.

Support is an essential service, a bridge between health and justice. We, governmental and non-governmental agencies, must have a strategic long-term approach; an approach which is agreed, and funded, at the national level in coordination with multiple victim support actors. We can then identify the victims, we can help them access the services they need, we can raise their awareness of existing services, and we can all work together more coherently. These are the aims of the National Framework for Comprehensive Victim Support.

At the highest level, we intend that every EU country has a national victims’ strategy, for there to be a minister with responsibility for victims’ issues. While many countries have existing security strategies, crisis infrastructure strategies, and environmental strategies, not many Member States have a victims’ strategy. However, a victims’ strategy must be underpinned by coordination and oversight mechanisms, and enforceable legal remedies, to ensure victims’ rights are fully implemented across Member States.

At a more detailed level, we have to work with victims, their social support networks, and with other actors that play a role in helping victims: with all the elements necessary for a national victim support network. We bring together all parts of society, so that no victim is forgotten, so that every victim’s needs are met coherently, efficiently and effectively. This is necessary or morally correct not only to meet State obligations to victims but also a logical decision since the benefits of victim support far outweigh their cost, allowing victims to recover from their experience and become a successful full member of society which reducing economic costs of crime, increasing productivity and increasing the successful operation of our justice systems.

Léa, it took you 1.5 years to research and write this paper, which is based on a three decades of experience built up by VSE: How do you feel now that the paper is finally finished?

Léa Meindre-Chautrand: I’m relieved it’s finally published! We’re hoping that the paper will allow people to understand that victim support is a more than poignant, touching attempt by civil society to try to meet people’s needs in difficult situations. We think that victim support requires acknowledgment, acceptance of a new way of thinking; that victim support is a combination of mechanisms and coordination by actors and sectors to deliver assistance (practical, legal, financial, medical, psychological) to those in need following a crime.

Léa Meindre-Chautrand: I’m relieved it’s finally published! We’re hoping that the paper will allow people to understand that victim support is a more than poignant, touching attempt by civil society to try to meet people’s needs in difficult situations. We think that victim support requires acknowledgment, acceptance of a new way of thinking; that victim support is a combination of mechanisms and coordination by actors and sectors to deliver assistance (practical, legal, financial, medical, psychological) to those in need following a crime.

While the implementation of successful support will always be challenging, many EU countries have moved forward to build cohesive national support systems. In France and Portugal, for example, the success of their victim support services is obvious, while Italy also provides a good level of victim support. Germany is a country that has positively come to terms with victims’ rights over the past 45 years and is now home to one of the oldest victim support organisations in Europe.

Our newly proposed model is based on existing best-practices and is delivered at a critical moment in the history of the EU. It takes a long time to create victim support systems, and it is a fragile process; it’s now been 10 years – a second in historical terms – since the Victims’ Rights Directive was adopted, and we now need to invest in long-term engagement and support to make sure the establishment of a European victim support system is successful. Our paper is a useful strategic approach for developing a more resilient society which supports victims’ rights across the EU.

Victim Support Europe (VSE) is an umbrella for 70 organisations that annually assist more than 2mln victims of crime. What role do VSE members play in shaping the European Union’s (EU) victims’ rights policy?

Léa Meindre-Chautrand: VSE’s members are the roots of our organisation, they help us develop our policy and they help with work on research. Our members include both generic and specialist victim support organisations, state institutions which host victim support services, and universities and organisations which work with victims in various settings. We consult with our members on a daily basis, we rely on their input and their knowledge of the challenges faced by victims. From our members we learn what works for victims, what it means for victims to receive support, and, for example, what takes to run a victim support helpline. The strength of our network lies in exchanging best practices and knowledge between organisations based in different countries. When members come together at our Centre of Excellence meetings or workshops, we see how they benefit from learning from each other. The expertise held by our members allows us to learn about victim support and the state of victims’ rights in different contexts.

Léa Meindre-Chautrand: VSE’s members are the roots of our organisation, they help us develop our policy and they help with work on research. Our members include both generic and specialist victim support organisations, state institutions which host victim support services, and universities and organisations which work with victims in various settings. We consult with our members on a daily basis, we rely on their input and their knowledge of the challenges faced by victims. From our members we learn what works for victims, what it means for victims to receive support, and, for example, what takes to run a victim support helpline. The strength of our network lies in exchanging best practices and knowledge between organisations based in different countries. When members come together at our Centre of Excellence meetings or workshops, we see how they benefit from learning from each other. The expertise held by our members allows us to learn about victim support and the state of victims’ rights in different contexts.

What does VSE hope to achieve by the launch of the ‘National Framework for Comprehensive Victim Support’?

Léa Meindre-Chautrand: The report is the outcome of research and consultations with EU and international victim support experts. Work began with the VOCIARE project, in which we analysed the implementation of the Victims’ Rights Directive across EU Member States. We then continued to develop a schematic which determined the roles played by different actors involved in providing support to victims of crime. We know from our members that, in countries where cooperation is well developed between different stakeholders, support is delivered in a coordinated manner.

Victims are the centrepoint to our national support framework, their needs and rights form the basis of our work; their empowerment, recovery from and regained confidence following the impact of a crime are key outcomes highlighted in the document. Educating – while at school or at work – citizens on what it means to fall victim to a crime and to understand the impact of a crime, empowers us to be more resilient, to be able to recognise signs of victimisation, and shows us how as individuals we can support victims of crime. Victims who are surrounded by friends, family, and colleagues are less likely to need professional help as their social circle acts as their support network.

Victims are the centrepoint to our national support framework, their needs and rights form the basis of our work; their empowerment, recovery from and regained confidence following the impact of a crime are key outcomes highlighted in the document. Educating – while at school or at work – citizens on what it means to fall victim to a crime and to understand the impact of a crime, empowers us to be more resilient, to be able to recognise signs of victimisation, and shows us how as individuals we can support victims of crime. Victims who are surrounded by friends, family, and colleagues are less likely to need professional help as their social circle acts as their support network.

Why are we talking about this? Because the reality is that we have to bring together all those working – separately – on behalf of victims; support should be delivered collaboratively within a system that ensures efficiency and allows trust to be developed. Our framework not only describes how the various services should deliver their support effectively but also suggests standards that they should follow; therefore, if one organisation is unable to provide appropriate support, the victim can be referred to another more relevant, trusted, service which complies to the same standards. We’ve been working on these standards for years and we encourage all our European members to apply them in their work.

We want to emphasise that support is everyone’s responsibility, not just that of victim support services. There are many professionals in contact with general population, representatives of civil society organisations but also of the justice system, who may encounter victims of crime in their work. So, based on their personal experience, how can they, for example, support a colleague who is a victim of crime? Private and public sector organisations must be open to learning about victims’ needs and rights, and how they can support victims, whether through training to identify signs of victimisation or organisational policies to support victimised members of their community. As individuals, we may decide to advocate at the parliamentary level, or simply listen to those who have been traumatised; no matter what we do, it is our responsibility to recognise victimisation, to offer the best support we can, connect victims with professional services, and ensure that our organisations are able to help victims of crime. The combination of all these different mechanisms and the coordination between actors and sectors will help to reduce secondary victimisation, to maximise the victims’ experience in the criminal justice system and, in general, will have the greatest impact on victims who need protection, support and justice.

We want to emphasise that support is everyone’s responsibility, not just that of victim support services. There are many professionals in contact with general population, representatives of civil society organisations but also of the justice system, who may encounter victims of crime in their work. So, based on their personal experience, how can they, for example, support a colleague who is a victim of crime? Private and public sector organisations must be open to learning about victims’ needs and rights, and how they can support victims, whether through training to identify signs of victimisation or organisational policies to support victimised members of their community. As individuals, we may decide to advocate at the parliamentary level, or simply listen to those who have been traumatised; no matter what we do, it is our responsibility to recognise victimisation, to offer the best support we can, connect victims with professional services, and ensure that our organisations are able to help victims of crime. The combination of all these different mechanisms and the coordination between actors and sectors will help to reduce secondary victimisation, to maximise the victims’ experience in the criminal justice system and, in general, will have the greatest impact on victims who need protection, support and justice.

As an expert, what is your advice to those who are trying to advance victim support in their countries?

Léa Meindre-Chautrand: We often work with countries which have little in the way of victim support facilities, to gather information and to prepare ourselves for the next research project: I suggest that any advocate working where there are failures under law and in the provision of victim support should read our ‘National Framework for Comprehensive Victim Support’ and take stock of the evidence collected in the report.

While much work will need to be carried out before their country’s national political agenda is advanced, the framework will offer the means to take victims’ support to the next level.

The report can be downloaded here.

DISCLAIMER: The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Victim Support Europe and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Union.